At a time when traditional African music was quickly disappearing and the African scales were being replaced by the Western scale, Hugh Tracey founded ILAM, an institution to preserve African music and to promote research into African music.

By the 1950’s, Hugh Tracey recognized a dire situation: western culture and pop music were spreading throughout the world and were making large inroads into indigenous populations and music, threatening to obliterate them. He realized it was time to make a widespread survey of African music.

So in 1952, he undertook the most extensive recording tours in Africa to date, spending most of the year in the field. Private funding he had obtained enabled him to travel with three helpers (a recording engineer, his assistant and a driver) and two motor vehicles, state-of-the-art recording equipment, an electrical generator, and a half mile extension cord.

Hugh was interested in all kinds of African music, but his favorite was kalimba music.

As Paul Tracey related to me, his father Hugh would drive down the road and look for telephone poles that were leaning over. He would then start asking around for musicians, (who would cut the guy wires and used them to make kalimba tines), and when he found them, the fun would begin. Paul recalled that Hugh would set up the generator out of hearing range of the village, connect it to his tape recorder with the enormous extension cord, and play for the villagers some music he had recently recorded from a nearby region. Appealing to human nature’s competitive side, he goaded them to do better than their neighbors could, and often inspired excellent performances. These outdoor recording sessions usually went late into the night.

Hugh Tracey came to recognize that the scales that were used on the kalimbas were not at all like the western scale on the piano – certain notes would fall in between the notes on the piano. Furthermore, he realized that there was a certain consistency in the scale used by a particular ethnic group. The scale consistency was enforced by the instrument makers who copying their own instruments and fine tuned them according to what they perceived to be the correct notes.

In order to document these unique scales, Hugh Tracey procured a set of microtonal tuning forks covering an entire octave with between 3 and 6 forks per half step interval.

While Hugh Tracey archived a lot of very important data on mbira and kalimba tunings across Africa, he did not achieve his big dream. He realized that the different types of kalimbas were related to each other in an evolutionary sense, similar to how different species of mammals are related to each other. He thought he could disentangle the branches of the kalimba family tree by studying the details of the tunings of the different instruments, just as evolutionary biologists can trace ancestry through genetic similarity.

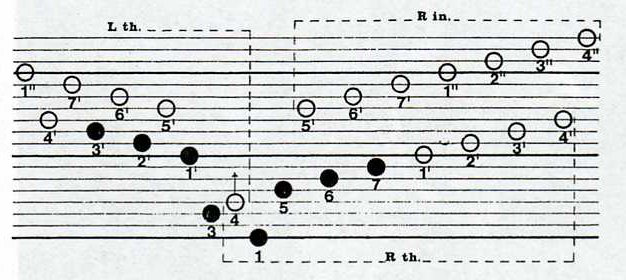

Even though Hugh Tracey never did develop a unified theory of kalimba evolution based on the different kalimbas’ tunings, his son Andrew Tracey did. Andrew identified eight notes (the filled circles in the diagram above) as the “kalimba core” and referred to an instrument with those notes as the “original mbira”. (The numbers refer to the degrees of the scale, so 1 =Do, 2 = Re, 3 = Mi,and 1′ = Do an octave higher.) The micro-tonal tuning adjustments that Hugh Tracey was so interested in are ignored in this view.

Almost every traditional kalimba variety in southern Africa includes these eight notes centrally. Other notes are added to bigger instruments by extending the tines outward (the lower open circles in the diagram) or by adding additional rows of shorter, higher-pitched tines (the upper open circles in the diagram).

By the way, if you are interested in learning about the “original mbira” first hand, Kalimba Magic sells a modern version under the name of the Goshen 9-Note Student Karimba. We also sell a

book for the student karimba, which includes many traditional African songs for this instrument, some of which were taken from Hugh Tracey’s sound recordings from the 1950s.

In 1954, Hugh Tracey founded the International Library of African Music (ILAM) to house his large and growing collection of recordings, documentary notes, and musical instruments. He saw ILAM as an institution that would support research into African music long after his own passing.

In an attempt to defray the costs of traveling and recording, ILAM entered into an arrangement with the Gallo record company which began distributing popular recordings of African music that Hugh Tracey had made in his travels, including the guitar work of Jean Bosco Mwenda. This music would be distributed around Africa and around the world.

Meanwhile, ILAM made another product available to music researchers and ethnomusicologists: a set of 210 LPs representing Hugh Tracey’s best field recordings of African music. The momentum of this enterprise led Hugh to make another grand recording tour in 1957.

One of the crowning achievements of ILAM was the African Music Journal, which published the research articles of Hugh Tracey and many other ethnomusicologists in a scholarly setting. The African Music Journal was first published in 1954 and is still published today. You can find it in many university libraries or at ILAM’s web site.

Hugh Tracey continued to serve as director of ILAM until his death in 1977. His son Andrew took over as ILAM director from 1977 until his own retirement in 2005. Diane Thram has been ILAM director since 2006.

Hugh Tracey blazed a new path, practicing ethnomusicology before the field was even recognized. He had no training, no college work – his only degree was an honorary doctorate from the University of Cape Town, South Africa. His great accomplishments originated with his love and respect for the African people and the music they made. May Hugh Tracey be an inspiration to all of us, reminding us that great things can be accomplished through love.

Hugh Tracey gathered recordings of traditional African music between the late 1920s and the 1960s. The recordings were edited and housed at ILAM, and eventually distributed to musicologists, universities, and enthusiasts around the world. These recordings formed a snapshot in history to document what was there before the encroachment of western music and musical values.

Diane Thram, director of ILAM since 2006, has begun the process or repatriating the field recordings to the communities from which they originally came. What a remarkable enterprise! In the video below, you will learn the story of how the song Chemirocha was brought back to the community who sang it decades ago. Some of the people who were present at the original recording are still alive. It is worth watching the video just to learn the meaning of the song’s title.

Sign up for our newsletter and free resources with your email address:

We pinky promise not to spam you and to only send good stuff.

Christmas in July 2025

Christmas in July 2025 Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba

Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba