A customer recently asked:

“I am having a lot of trouble playing my kalimba. I took piano lessons as a child for three years and I think this is the trouble. Is there a tip to help me make sense of reading the kalimba music as opposed to reading piano music?”

The kalimba and the piano are very different instruments! Two big differences between them are that the kalimba only has a small subset of the notes the piano has, and the notes on the kalimba are arranged in a way that is fundamentally different from the arrangement on the piano.

While the general music introduction you got from piano lessons will be helpful on your kalimba journey, the specific muscle memory (and the way you think about reading and playing music) that you developed from playing piano is pretty much irrelevant to playing the kalimba.

Not every kalimba is a diatonic kalimba, but most kalimbas you can find today are diatonic kalimbas. “Diatonic” is a fancy word that means the kalimba has only the notes in some major scale – you know, “Do Re Mi Fa So La Ti Do.” It can have one octave, two octaves, or more, but it must have all of these notes, and it will have no other notes. There are five places where other notes (flats and sharps) fall in between these notes – in between “Do” and “Re” for example. These are the “black notes” of the piano, and they are missing on a diatonic kalimba.

Speaking of which: a simple way to think about diatonic kalimbas is that they have just the white notes from the piano – C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C – but no black notes such as F#/Gb (the little “b” indicates a flat) or C#/Db. A kalimba that has all of the notes, both white notes and black notes, is called a chromatic kalimba.

The key of G has one sharp in it, the F#. This means that the Alto in G has that F#, but the type of scale the Alto kalimba plays is the same as the type of scale played by the white notes of the piano – Do, Re, Mi, Fa, So La, Ti, Do. The Hugh Tracey Alto kalimba is a diatonic instrument. So, while it has a sharp in its scale, it plays the diatonic G scale. The takeaway: You can have a diatonic kalimba in any key, and you think of the kalimba as if it were just the white notes on the piano.

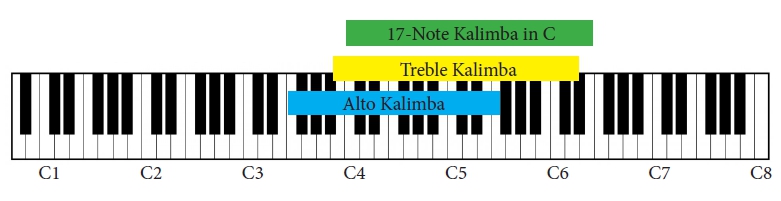

Another obvious difference between the piano and the kalimba is the range, or the distance between the lowest and highest notes. The kalimba is not only missing several notes in between the notes it plays, but the kalimba’s notes do not go very low or very high. A typical 17-Note Kalimba in C ranges from C4 to E6, while the 88 note piano ranges from A0 to C8 (The numbers represent the octave on the piano. A0 is lowest note. C4 is middle C, and there are 8 octaves.) The limited range of the kalimba becomes an issue because some melodies will not fit nicely on the kalimba, and if you are trying to arrange common piano music (ie, melody and lower note accompaniment), you will have to make some accommodations on the kalimba – for example, the piano’s left hand notes may need to be transposed up an octave or two, or otherwise modified, to fit on the kalimba.

Another obvious difference between the piano and the kalimba is the range, or the distance between the lowest and highest notes. The kalimba is not only missing several notes in between the notes it plays, but the kalimba’s notes do not go very low or very high. A typical 17-Note Kalimba in C ranges from C4 to E6, while the 88 note piano ranges from A0 to C8 (The numbers represent the octave on the piano. A0 is lowest note. C4 is middle C, and there are 8 octaves.) The limited range of the kalimba becomes an issue because some melodies will not fit nicely on the kalimba, and if you are trying to arrange common piano music (ie, melody and lower note accompaniment), you will have to make some accommodations on the kalimba – for example, the piano’s left hand notes may need to be transposed up an octave or two, or otherwise modified, to fit on the kalimba.

But the most essential difference between the kalimba and the piano is the way the notes are laid out. The piano has a linear note arrangement. The low notes are on the left and the high notes are on the right. There is no ambiguity. You can actually calculate exactly where each note should be. It is totally logical. When learning to play piano, your brain comes to internalize this structure – a direct correlation of pitch and location on the piano keyboard. Additionally there is a very clear and simple relationship between notes on the linear staff notation and the linear note arrangement on the piano.

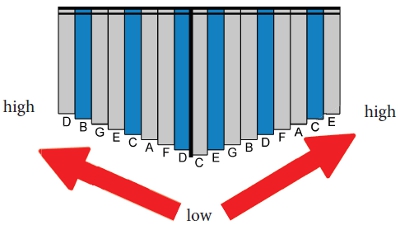

But the kalimba has a bi-linear note arrangement. The low notes are in the center, while the higher notes will be on the far left AND the far right. Looking at the diagram at the top of this article, you can see that half the white notes end up on the right side of the kalimba, with higher notes to the right; and half the white notes end up on the left side of the kalimba, with higher notes to the left – and that is topsy-turvy compared with everything you learned on the piano.

Here are some of consequences of this arrangement. In the diagrams below, be sure to refer to the note names at the bottom of the tablature.

The right side of the kalimba is parallel with the piano’s keyboard – the farther right you go, the higher you go. The left side of the kalimba is the reverse of the piano’s keyboard – as you go farther left, you go to higher notes. This makes for a bi-directional note arrangement that fundamentally transforms how you think about creating music, and the sorts of motions you will need to make to accomplish some particular musical idea.

The right side of the kalimba is parallel with the piano’s keyboard – the farther right you go, the higher you go. The left side of the kalimba is the reverse of the piano’s keyboard – as you go farther left, you go to higher notes. This makes for a bi-directional note arrangement that fundamentally transforms how you think about creating music, and the sorts of motions you will need to make to accomplish some particular musical idea.

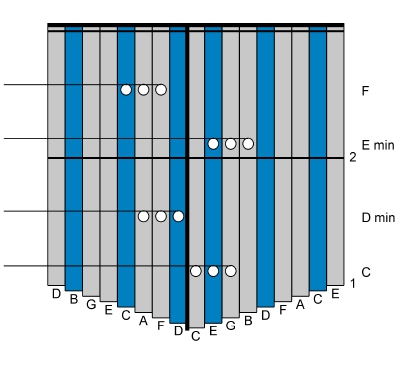

If you play three adjacent notes on one side, you will get something like: 1 – 3 – 5, or 2 – 4 – 6, or 3 – 5 – 7. These are all going to be beautiful chords. In other words, the recipe for how to arrange the notes on the kalimba is sort of the same as the recipe for making diatonic chords.

If you play three adjacent notes on one side, you will get something like: 1 – 3 – 5, or 2 – 4 – 6, or 3 – 5 – 7. These are all going to be beautiful chords. In other words, the recipe for how to arrange the notes on the kalimba is sort of the same as the recipe for making diatonic chords.

Look at the chord diagram. The C chord is made by playing the lowest three tines on the right, C – E – G. But notice the C – E – G in the middle of the left side. (In reverse order, G – E – C.) This is important: upper octave notes are on the opposite side of the kalimba from the lower octave notes.

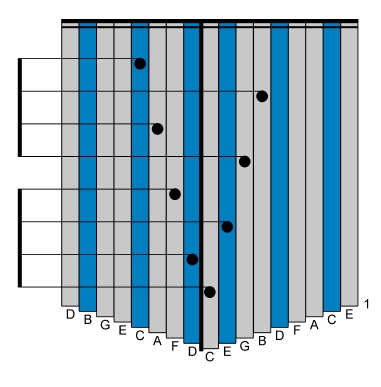

To play a scale on the kalimba, you have to zig-zag back and forth. Most melodies contain segments of the scale, which means that you will need to get good at playing the scales. In a way, the scale is one of the more difficult things on the kalimba, because you jump from the right side, to the left side, and back to the right side. This is relatively easy when you are at the low notes in the center of the kalimba, as you don’t have to jump very far. However, as you go higher and higher on the kalimba, each jump from side to side becomes larger, and more prone to error. But it’s also simple:

To play a scale on the kalimba, you have to zig-zag back and forth. Most melodies contain segments of the scale, which means that you will need to get good at playing the scales. In a way, the scale is one of the more difficult things on the kalimba, because you jump from the right side, to the left side, and back to the right side. This is relatively easy when you are at the low notes in the center of the kalimba, as you don’t have to jump very far. However, as you go higher and higher on the kalimba, each jump from side to side becomes larger, and more prone to error. But it’s also simple:

Hint: when going up or down the scale, don’t think of crossing from one left tine a long way over to a tine on the right side. Rather, remember where each of your thumbs last played a tine. The next tine your left thumb will play will be one tine over from the one it last played.

Crossing sides on the kalimba is problematic, but the kalimba-painting scheme is made to help you out here. See the middle C, in the middle of the left-side tines? That is a painted tine. To go one note higher in the scale, to D, you need to cross over the middle to the D on the left side. That D is also a painted tine. Also, the high B on the far left, is one note below the painted high C on the far right.

That is a general rule: the painted tines come in pairs, and for each pair of tines, the painted tine on the left side is always one pitch lower in the scale than its corresponding painted tine on the right.

So, as you zig-zag your way up and down the scales, pay attention to where your thumbs are moving over the painted and unpainted tines. They are guideposts that will help you remember where you are on the kalimba, where to play, and how to stitch together the left and right sides of your kalimba!

A common misconception made by people who at first look quickly at the kalimba without thinking, is that perhaps the painted tines work like the black keys on the piano. This is not so – we already discussed that the kalimba has just the white notes – or even if it is in a different key than C, it is conceptually the same as just having the white notes. The painted tines are simply a way to help you keep your place on the kalimba and to interface the left and right sides. And, when using kalimba tablature (invented by me in 2004), those painted tines are extremely useful when learning to play what you see in tablature, ie, transferring notes from tablature to kalimba.

A short answer is this: staff notation directly shows the pitch, which is simply related to the linear way the notes on the piano are laid out. Kalimba tablature maps directly into the physical tines on your kalimba that you need to pluck to play the song. We have another blog post, “Why Kalimba Tablature,” that goes into this in great detail.

Staff notation tells you how the music sounds. Kalimba tablature shows you what tines you need to play on the kalimba to make that music.

Oh, and staff notation reads across the page left to right, while kalimba tablature reads UP the page, from bottom to top. Tablature looks exactly like the actual kalimba and is a function of physical location AND time.

I find my kalimba tablature has the most simple mapping of any notation system used for the kalimba.

The inconvenient part of using kalimba tablature is that every kalimba type needs its own book or set of books (although the tine-painting scheme can make instructional materials more widely applicable, in some cases). But the great thing about it is that virtually anyone can learn to play using kalimba tablature fairly quickly.

Sign up for our newsletter and free resources with your email address:

We pinky promise not to spam you and to only send good stuff.

Christmas in July 2025

Christmas in July 2025 Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba

Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba