For 6 months, I was the sole worker at Kalimba Magic. I wrote the newsletters, wrote the books, I answered the phone and took the orders, maintained inventory, assembled, tuned and painted kalimbas, and packed and shipped.

This work was a great time for me. A Zen-like focus on my craft resulted. I surely came out of this period a better human.

When I recently hired Kacy Todirita to help with the kalimba business, there was suddenly enough slack in my schedule that I decided to try and change my life a bit. I would wake at 5 AM, chores till 6, walk with my kalimba till 7, and then every morning, I would record music. I would try this new life on for 100 days.

Well, what do you think happened with this highly structured plan?

Read on and learn the story of the music you are hearing right now (also in the player at the bottom of this page).

I won’t go into the details of the failure of my great plan, but I was having trouble recording in so structured a schedule. I would come in from my walk, brand new song or a revived older song in my hands and mind, ready to record, and boom! I didn’t feel like doing it.

On the days that I did record, I was obsessed with perfection – with creating a perfect rhythm track, and a perfect performance of the music that had been freely flowing out of me as I had kalimba-walked in my neighborhood only an hour earlier. No wonder I never felt like doing it.

You have heard stories like this before – about how someone freezes or chokes, and it is oh-so-sad for the otherwise wonderful but now noncreating artist.

But I share this story with you because I want you to know about the necessary flip side of the Mark Holdaway I tend to put out to the world, the guy who knows everything and can play 20 different kalimbas to within 0.1% accuracy.

I had all of these cerebral plans – but in order to get anything out, I had to let go of those plans. Instead of recording this kalimba part for that song for this important reason, instead of following my head, I had to learn to follow my heart. I had to record some music just because. Just for the fun of it.

I reached blindly for a kalimba – not the one I had been rehearsing on, but a kalimba that shouldn’t even have been in the studio – my Box Pentatonic Kalimba in F7 Bebey tuning. It just sort of called to me. This is the tuning that Francis Bebey used for his song “Breaths,” which includes the lyrics “Listen more often to things than to beings / ‘Tis the ancestors’ breath when the fire’s voice is heard.” It is a wild tuning. And it was exactly what I needed.

No plan. It was a bit like the first time I jumped off the high dive at the pool when I was a kid. After weeks of being afraid to do it, I just got in line, calmly climbed up the ladder, walked to the spring board, pretended to be fearless – and in that instant I WAS fearless – and I jumped as high as I could, and hit the water at slight angle, hurting my head and stomach a bit… but I had done it!

Once you have done the groundwork, once you have learned your stuff and know what you want to do and what you are all about, there is nothing holding you back but yourself.

So, at that moment I got out of the way. I just let the kalimba say its piece in its own voice. No plan. No idea. No song. No tempo. No chord progression. No melodic motif, just the immediacy of the kalimba softly breathing in my hands. Just the clear, piercing sound of the kalimba. In this dance, kalimba led and I followed.

Part of the success of the moment came from the exact kalimba I picked up – a pentatonic kalimba. “Real” musicians might put down pentatonic instruments as toys, but these instruments do point to the ancients.

The pentatonic scale is any of several five-note scales – that is, five notes in each octave. There are actually several different pentatonic scales. The most common pentatonic scale – the major pentatonic scale – resembles the diatonic major scale (the one we know as “Do Re Mi Fa So La Ti Do”), but it is missing some notes – the Fa and the Ti (the 4 and 7). This leaves “Do Re Mi — So La — Do” – which is six notes because we repeated the Do at the top of the scale. Notice the black keys on a piano have the same pattern: three notes, space, then two more notes. If you start on F#, the piano’s black keys will make this pentatonic scale.

Removing the 4 and 7 means that there are no half-step intervals between adjacent notes in the scale. (Some pentatonic scales, such as the Japanese Ake Bono scale, do have half-step intervals.) Without half-step intervals, the potential for nasty dissonance is greatly reduced. This benefit is balanced by the drawback that melodic and harmonic possibilities are also reduced.

The F7 Bebey pentatonic tuning is pretty unique. It is similar to the major pentatonic scale , but has a minor 7th instead of a 6th, which makes it sound oh-so-cool!

The earliest known musical instrument on earth is a 40,000 year old bone flute with five holes… and it plays the pentatonic scale! In the 1950s, ethnomusicologist Hugh Tracey reported that about 40% of the kalimba tunings he documented in the field were pentatonic tunings. In other words, humans have probably spent the vast majority of music-making history playing pentatonic music.

There have long been many peoples in Africa making more complex kalimbas with 6- and 7-note scales, and playing more complex music. But it isn’t always about complexity. Sometimes it is just about emotion, and the pentatonic scale is a good place to connect with and channel that emotion. There is something raw and wild and freeing – even primitive – about playing in pentatonic scales. But when I make music on these “primitive scales,” I am touched by just how much emotional sophistication is possible. The sound of the kalimba playing on this page expresses a bit of that potential.

And if you ever feel stuck within your mind and all of its ideas and problems and plans and demands – and ultimately, limitations – you might just want to open up a forgotten door and check into some pentatonic music.

Sign up for our newsletter and free resources with your email address:

We pinky promise not to spam you and to only send good stuff.

Christmas in July 2025

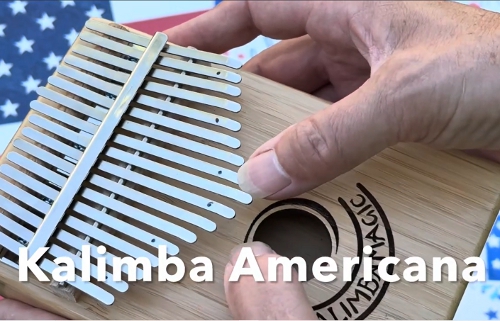

Christmas in July 2025 Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba

Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba