The kalimba has a rich and varied history in Africa that stretches back as much as 3000 years, but the metal tined kalimba is only about 1300 years old. The modern kalimba player can learn a lot from the strands of traditional African kalimba music.

First, some nomenclature: there are over 100 different types of traditional African thumb pianos, and mbira, kalimba, sansa, and karimba are among them. In 1954 Hugh Tracey chose one of those names, kalimba, for the version of the instrument he would soon ship around the world. In 1961, he also wrote an article, “The Case for the Name Mbira”, suggesting that we use mbira as a generic name for any traditional African thumb piano. Today, outside of Africa, kalimba is also used generically for any non-traditional thumb piano.

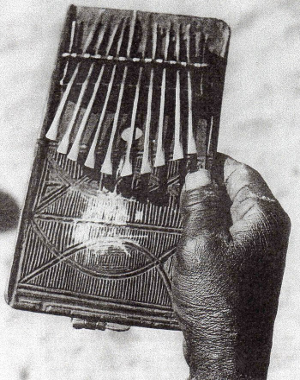

The first European to record seeing the mbira was Portuguese explorer and missionary Father Dos Santos who was in present-day Mozambique in1586. He documented the playing of the 9-note iron-tined instrument he called “ambira”. The players would grow their thumb nails long to play, and the instrument produced a “sweet and gentle harmony of accordant sounds”. As these instruments were not very loud, they were generally played in the king’s palace.

By the way, Andrew Tracey believes he knows the notes this 9-note kalimba was tuned to.

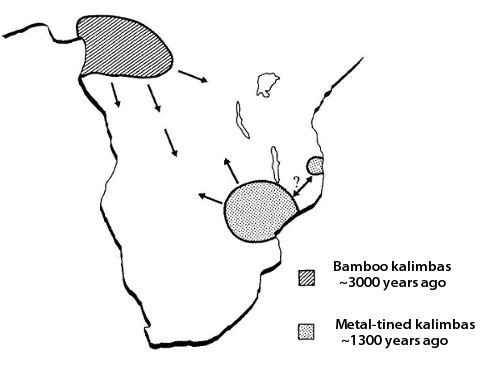

By 1586 when Father Dos Santos documented the kalimba, it was already an ancient musical instrument. Gerhard Kubik, in his 1998 book Kalimba, Nsansi, Mbira: Lamellophone in Afrika, makes the case for the kalimba being invented twice in Africa: The first kalimbas were made about 3000 years ago in west Africa around present day Cameroon, created completely of plant materials such as bamboo. Then around 1300 years ago, when the Iron Age reached the Zambezi valley in southeastern Africa, someone got the bright idea to make kalimba tines out of metal.

By 1586 when Father Dos Santos documented the kalimba, it was already an ancient musical instrument. Gerhard Kubik, in his 1998 book Kalimba, Nsansi, Mbira: Lamellophone in Afrika, makes the case for the kalimba being invented twice in Africa: The first kalimbas were made about 3000 years ago in west Africa around present day Cameroon, created completely of plant materials such as bamboo. Then around 1300 years ago, when the Iron Age reached the Zambezi valley in southeastern Africa, someone got the bright idea to make kalimba tines out of metal.

Traditional style kalimbas are still made today in Africa with tines of both plant matter and the louder, longer sustaining metal. The plant matter kalimbas, often made from bamboo, do not sustain for very long and do not currently have much of a consumer market. I have seen a few at UN stores.

Traditional style kalimbas are still made today in Africa with tines of both plant matter and the louder, longer sustaining metal. The plant matter kalimbas, often made from bamboo, do not sustain for very long and do not currently have much of a consumer market. I have seen a few at UN stores.

The Iron Age reached southern Africa around 1300 years ago, and Africans were quite skilled at smelting and fashioning iron. It is Gerhard Kubik’s hypothesis that metal-tined kalimbas started to be made in the Zambezi River Valley shortly after the people there started to use iron. During the years that European powers held African lands as colonies, Africans were discouraged from making their own metal, so kalimba tines were made out of nails, bicycle spokes, or other scrap metal pounded flat. Most modern kalimbas, starting with the Hugh Tracey kalimbas in 1954, use plated spring steel for the tines.

The Iron Age reached southern Africa around 1300 years ago, and Africans were quite skilled at smelting and fashioning iron. It is Gerhard Kubik’s hypothesis that metal-tined kalimbas started to be made in the Zambezi River Valley shortly after the people there started to use iron. During the years that European powers held African lands as colonies, Africans were discouraged from making their own metal, so kalimba tines were made out of nails, bicycle spokes, or other scrap metal pounded flat. Most modern kalimbas, starting with the Hugh Tracey kalimbas in 1954, use plated spring steel for the tines.

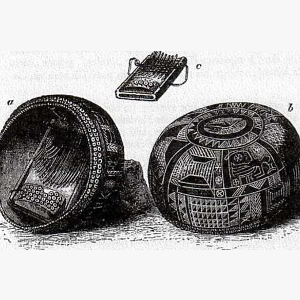

In the Zambezi Valley, around present-day Zimbabwe, mbiras evolved into diverse, complex instruments with a rich musical tradition, which is highly integrated into the culture. While simple instruments with 6-10 tines are found widely in sub-Saharan Africa, the Shona people in present-day Zimbabwe created the mbira dzavadzimu, the “big mbira of the ancestral spirits”, with 21-25 tines, which played a central role in their religion, helping people keep in contact with their ancestors. This supports Kubik’s assertion that the metal-tined mbiras originated here, far from where the Portuguese first saw them. The illustration to the left shows: a) the mbira with shell buzzers, b) the deze, a gourd amplifier for the mbira, and c) the sanza, a smaller instrument. This drawing was made by an artist on explorer David Livingstone’s expedition across southern Africa, c.1854.

In the Zambezi Valley, around present-day Zimbabwe, mbiras evolved into diverse, complex instruments with a rich musical tradition, which is highly integrated into the culture. While simple instruments with 6-10 tines are found widely in sub-Saharan Africa, the Shona people in present-day Zimbabwe created the mbira dzavadzimu, the “big mbira of the ancestral spirits”, with 21-25 tines, which played a central role in their religion, helping people keep in contact with their ancestors. This supports Kubik’s assertion that the metal-tined mbiras originated here, far from where the Portuguese first saw them. The illustration to the left shows: a) the mbira with shell buzzers, b) the deze, a gourd amplifier for the mbira, and c) the sanza, a smaller instrument. This drawing was made by an artist on explorer David Livingstone’s expedition across southern Africa, c.1854.

In the Zambezi Valley, around present-day Zimbabwe, mbiras evolved into diverse, complex instruments with very deep music which is highly integrated into the culture. While simple instruments with 6-10 tines are found widely in sub-Saharan Africa, the Shona people in present-day Zimbabwe created the mbira zdavazdimu, the “big mbira of the ancestral spirits”, with 21-25 tines and a central role in their religion, helping people keep in contact with the ancestors. This supports Kubik’s assertion that the metal-tined mbiras originated here, far from where the Portuguese first saw them. The illustration above of a) the mbira with shell buzzers, b) the deze, a gourd amplifier for the mbira, and c) the sanza, was made on David Livingstone’s expedition across southern Africa, c.1854.

As the mbira spread across Africa, separate clans or tribes each created their own version. As time passed, each group made modifications to the instrument design, such as how many tines the instrument had or what sort of board or gourd was used for mounting the mbira. Mbiras were also given special tunings by each group to support their unique music. The kalimba/mbira is a truly flexible instrument.

One important path of proliferation of these instruments developed when enslaved Congolese were moved around Africa and used as porters (basically, human pack animals) by their Belgian captors in the late 1800s and early 1900s. These people carried their own kalimbas and introduced them to many new groups of Africans who had never seen them. The Bushmen of the Kalahari Desert, isolated and nomadic, were not exposed to the kalimba until the 1950s.

In addition to wide variation in design and sound of the instrument, each group of people used the mbira differently in their social lives. In some African cultures, the mbira (and its modern descendant the kalimba) is the personal instrument of choice, something to take with you to help you pass the time tending cattle or riding the bus. In some places, it is an instrument of celebration for weddings, or an instrument to play for kings. It is used widely as an instrument to accompany the voice. One saying goes: “Kalimba without singing is like rice without beans”. And in some societies, it is a tool to attract the spirits of ancestors, to bring them back for a time so that their advice might be heard.

The history and pre-history of the kalimba/mbira are diverse and rich. Standing in the 21st century, we can choose to look into the past and learn the traditional songs, or we can choose to look forward and invent something new, just as the Africans have done all along. I choose to look both forward and backward, and I have found that it makes my kalimba experience that much richer.

Sign up for our newsletter and free resources with your email address:

We pinky promise not to spam you and to only send good stuff.

Christmas in July 2025

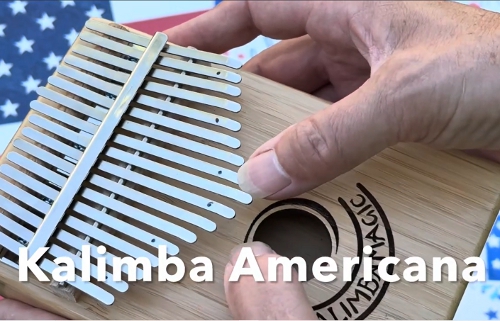

Christmas in July 2025 Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba

Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba