The kalimba, with its unique bi-directional note layout, makes playing scales a bit difficult because you have to zigzag your way up and down the tines, plucking first one on the right side, then one on the left, then the right, and working your way up or down the scale. It is easy zigzagging at the bottom of the scale, where the tines are close together in the center. The higher you go, the higher the chance of misplacing a finger, and zagging where you meant to zig. Fortunately, the painted tines will help guide you (a painted right tine is one note higher than the corresponding painted left tine), but this is still the most common type of error.

The flip side of the difficult scales is the easy chords. What makes it hard to play scales makes it simple to play chords. Chords on kalimba are really easy. Compared with the guitar, every one of whose chords has a different geometrical shape, the kalimba is painless – all the chords have basically the same shape.

Learning to drive the chords on your kalimba can tap into the most wonderful music this little instrument has to offer…

First of all, what is a chord? A chord is usually three or more notes that sound good together in some particular characteristic way. Different types of chords have different ways of sounding good together, and have different functions.

That is the first reason why you should learn chords: instead of painting with every color in the box, you can make superior music by focusing mainly on certain colors (notes) that have a proven track record of working well together… and then after a bit, switch to another set of notes that sound great, but in a different way.

But a chord comes out so much more clearly when you put the root in the bass.

Huh?

A triad is made up of notes 1, 3, and 5. The 1 note of a chord is also called the root of the chord. The root of the G chord is G. The root of the E minor (Em) chord is E.

A triad is made up of notes 1, 3, and 5. The 1 note of a chord is also called the root of the chord. The root of the G chord is G. The root of the E minor (Em) chord is E.

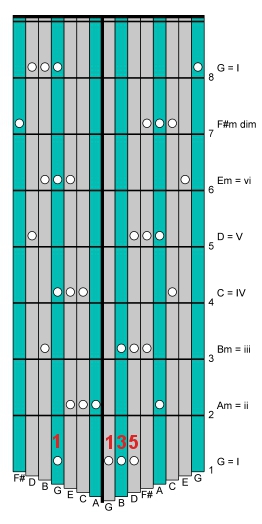

I direct your gaze to the footer of the tablature to the right – the note names are written out there. Chords basically skip every other note in the scale. The G chord contains G (1), it skips A (2), it includes B (3), it skips C (4), and it includes D (5). On the kalimba, those notes G, B, D, or 1, 3, and 5, are right next to each other. That is what makes kalimba chords easy. Of course, to play those three notes at the same time, you need to slide your thumb nail across those three adjacent tines, making a glissando. Or you could arpeggiate the chord, playing the notes one at a time – just like the guitar technique of “fingerpicking”.

And just to keep you on your toes, I have also included a single note on the opposite side of the instrument. For the G chord, that is the G note. It is the 8th note of the scale, but it is also the 1, the root note, just up an octave from the low root.

Following these chords up the tablature and up the scale, playing the triad on one side and the octave of the root on the opposite side, will make a pattern I call “the windshield wiper method” – can you see why?

Rule of thumb: to play the X chord, find the note X on the kalimba. Play that tine, plus the two adjacent shorter tines (higher notes). Don’t worry about major or minor for now.

When you play chords, or the notes from a chord individually, you automatically sound like you know what you are doing. The tablature here merely introduces the chords, and you are zigzagging up the scale, but in chords and not individual notes.

The Roman numeral system of chords is not tied to any key, but is an abstract representation that is more transparent for music theory purposes. It is well worth learning. You’ll know a chord is a major chord if it is written in the usual capital letters that make Roman numerals, and minor chords are represented by lower case letters.

On the Alto kalimba in standard tuning, G is the tonic, the I chord – it is home. Am is the ii (the “two minor”) chord, usually a transition chord. Bm is the iii (the “three minor”) chord. C is the IV chord, which is structurally important in many songs. D is the V chord – and it is only a mild overstatement to say that all of western harmony turns on the V chord. Em is the vi chord, important in that it is the relative minor to G major. And F#m dim is vii dim, a slippery chord indeed.

After you are able to play the four-note versions of these chords, work on these exercises:

And finally, I would like to inspire you to the lofty goal of playing both a melody on the short upper tines and a two- or three-note chord on the lower tines, usually opposite the melody note at that instant. This is something that you can experiment on and work out on your own – or you could jump into the extensive library of kalimba tablature we have created for the Alto kalimba.

Sign up for our newsletter and free resources with your email address:

We pinky promise not to spam you and to only send good stuff.

Christmas in July 2025

Christmas in July 2025 Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba

Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba